Johari’s Window: The Solution To Any Debate

Looking back, the third vivid debate between Secretary Clinton and now President Trump has been one of the most tense efforts to communicate politics in American history. During the transcript, the moderator, Chris Wallace was constantly cut off when trying to lend an appropriate amount of time for the two individuals to answer the questions.

WALLACE: Thank you, Secretary Clinton. I want to follow up…

TRUMP: Chris, I think it’s…

WALLACE: OK.

TRUMP: I think I should respond to that. First of all, I had a very good meeting with the president of Mexico. Very nice man. We will be doing very much better with Mexico on trade deals. Believe me. The NAFTA deal signed by her husband is one of the worst deals ever made of any kind, signed by anybody. It’s a disaster.

Hillary Clinton wanted the wall. Hillary Clinton fought for the wall in 2006 or thereabouts. Now, she never gets anything done, so naturally the wall wasn’t built. But Hillary Clinton wanted the wall.

WALLACE: Well, let me — wait, wait, sir, let me…

TRUMP: We are a country of laws. We either have — and by the way…

WALLACE: Now, wait. I’d like to hear from…

TRUMP: Well — well, but she said one thing.

WALLACE: I’d like to hear — I’d like to hear from Secretary Clinton.

CLINTON: I voted for border security, and there are…

TRUMP: And the wall.

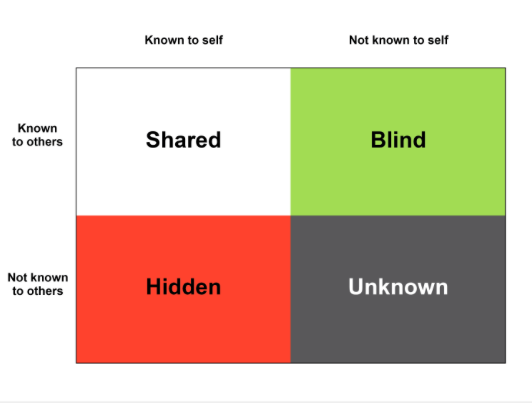

Today’s dilemma in politics substantially has to do with how people listen to each other. In a debate, it is crucial to know what each individual is saying before blurting out an argument that has only the context supported by the thoughts inside someone’s mind. A psychological term, called Johari’s Window, is used to explain the blind spots one may have when talking to other people, and the conscious and subconscious areas of one’s life. The window is made up of four basic forms of self: the public, the private, the blind, and the undiscovered. The “public” is what someone everyone to see and that person does not mind people discussing this part of them. The “private self” or “hidden self” is what a person would allow only themselves to see. One may choose to keep something hidden because the information is shameful or makes that person vulnerable. The “blind self” is what one does not see, but onlookers do. “You might see yourself as an open-minded person, when, in reality, people around you consider you an anatomical posterior” {as mentioned in the article “Liberal’s or Conservatives: Who’s Really Closed-Minded?” by Andrew G.}. Sometimes other people may not tell a person what they see in them because they are scared of being offensive, or they believe it is a waste of time. There is no way of a person knowing what is in their “blind self” unless the onlooker tells them. The last form of self is the “undiscovered” or “unknown”. This form is not only what oneself can not see, but others can’t either.

What makes Johari’s Window helpful in social situations, including debates, is that it demonstrates what each side can see in each other. There is the obvious, and there is the unknown, but what starts miscommunication is the incapability to share with one another the “private” and the “blind” self. Without sharing, there is no way that the “public” self can grow. Especially in debates like the presidential and ones on televised news, the participants never give each other the chance to share their expertise without fully listening.

Most people, whether conservative or liberal, tend to take note of the opposing argument as less open minded as their own. If that is so, where is the proof? “The University of Virginia Professor Jonathan Haidt’s new book The Righteous Mind doesn’t simply suggest that conservatives may not be as close-minded as they are portrayed. It proves that the opposite is the case, that conservatives understand their ideological opposite numbers far better than do liberals” {“Liberal’s or Conservatives: Who’s Really Closed-Minded?” – Andrew G}. What Haidt’s book does not do, is suggest that the solution to the argument between who is smarter, liberals or conservatives, is the simple study of Johari’s Window. All one would need to do in order to discontinue the argument, is share what each side knows is fact. All of the “blind selves” of each party would gather up to make the “public self”, and that is exactly how one would be able to solve the issue. Yes, opinions are a valid point to worry about, but opinions are based off of one’s personal experiences. If someone would share their experiences with another, and explain why their belief is so, the other person, if listening, will be able to partially understand why they feel that way.

In the battle of wits between two parties, or two people in a debate, the answer is strait forward, and Johari’s Window is the clear solution.

Lillian Simons, a junior this year at Westhampton Beach High School, is originally from Columbia, Illinois. As she got older, she grew up in Westhampton...